A DEEPER DIVE: To Understand More ….

Make a Donation

Get Involved

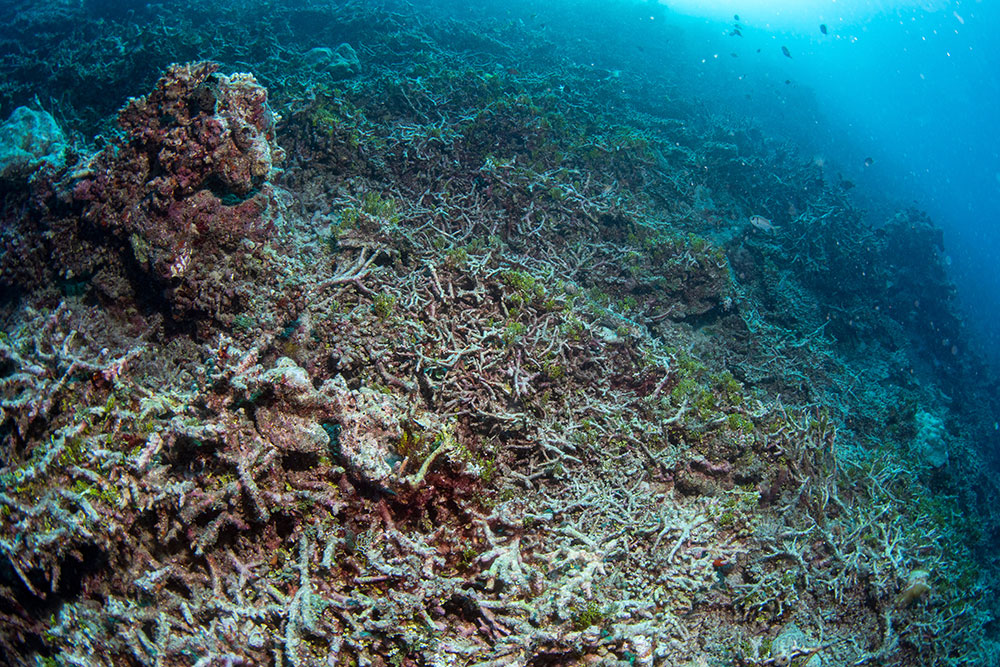

Coral Reef Ecosystems

Coral reef ecosystems are restricted to the sea floor and are one of the richest natural ecosystems in high organism abundance, species diversity (number of kinds of organisms), and role of interspecies interactions (symbioses). Coral reefs exist mainly in shallow, tropical waters, but can also be found at great depths in cold water. One particular feature of coral reefs is the role of colonial organisms, particularly corals (Phylum Cnidaria) that build thick and extensive frameworks of intergrown calcium carbonate skeletons. This framework provides a three-dimensionally complex structure in which many other species of invertebrate animals, marine plants (algae, seas grass), and vertebrates (fish, turtles, even birds) find homes and food. At the heart of the frame-building process is a unique symbiosis between single-celled microscopic green algae (zooxanthellae) that live within the body tissues of many host coral species. With exposure to penetrating sunlight, these algae live by photosynthesis that produces a great deal more food (carbohydrates) than the algae need for their basic survival, growth, and reproduction. The excess productivity is transferred within the coral to form the main energy source for the coral, enabling greatly increased growth and formation of the calcium carbonate skeleton.

Corals that lack this symbiosis with zooxanthellae cannot form reef structures, but they can exist in reef communities and also at great depths where light does not penetrate, or in colder waters that are not favorable for the symbiotic algae. The largest and most diverse coral reef ecosystems (such as the Great Barrier Reef or mid-oceanic atolls) actually thrive in warm (>18oC, shallow tropical seas (< about 60 m depth) where nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus and suspended food like phytoplankton and zooplankton are sparse (so-called oligotrophic waters). Coral reef waters are generally very clear (low turbidity) and have normal marine salinity (~35o/oo), but reefs can exist even in turbid waters, and experience salinity fluctuations from hyposaline (from influx of rivers or rainfall) to hypersaline (from evaporation in very shallow zones).

Corals

Corals are the principal animals that construct the reef framework that is the basis for a coral reef. Corals are not very familiar to most people because they live on the sea bottom usually in the tropics and belong to a large group of invertebrates (Cnidaria) that most people do not encounter. The most familiar cnidarians are “jellyfish” and sea anemones, but also include “soft corals”and “hard or stony corals”. All cnidarians have unique stinging cells with contain nematocysts in the tentacles. When injected into prey animals, nematocysts immobilize the prey that is taken into the mouth by the tentacles. These same nematocysts can cause painful, even lethal injuries by jellyfish, such as the Portuguese “Man-o-War” and “fire corals” known to swimmers and divers. The simplest coral has a soft-tissue body (polyp) much like a sea anemone that attaches to the sea bottom by a basal disk and has a cylindrical form topped by a circular oral disk with a ring of tentacles surrounding the mouth. Unlike anemones, the coral polyp deposits a calcium carbonate skeleton beneath its basal disk that can form a cuplike corallite. Corals can have a single polyp (solitary) or multiple, closely spaced corallites (compound), sometimes forming very large, boulderlike or massive structures (colonies) that grow together to form a reef framework.

Scleractinia (Stony corals)

Octocorallia

Echinoderms

Echinoderms are marine invertebrates constituting the Phylum Echinodermata that are diverse and abundant as reef-dwelling marine animals. Echinoderms include five major groups (classes): sea stars (Asteroidea), sea urchins (plus heart urchins and sand dollars – Echinoidea), brittle stars (Ophiuroidea), sea cucumbers (Holothuroidea), and feather stars (Crinoidea), and all occur on coral reefs. The body plan of all echinoderms has five-part (pentameral) symmetry, best known in the 5-armed seas stars and brittle stars. Echinoderms form calcium carbonate skeletons in the form of plates, spines, and other complex parts such as arm “ossicles” of sea stars and crinoids.

Crinoids

Living crinoids exist in two body forms: the “sea lily” that attaches to the sea bottom by a “stalk” composed of disk-like plates called columnals and a root or holdfast and the stalkless “feather star”. The “crown” at the top of the stalk consists of the body with the mouth directed upward and surrounded by five “arms” that usually branch and bear shorter branches called pinnules. The arms and pinnules carry a gutter-like “food groove” that is lined with tiny tentacles (“tube feet”) that are used for capture of suspended food particles and also respiration by means of absorption of dissolved oxygen through a thin tissue wall and excretion of dissolved CO2.

Macroinvertebrates

Macroinvertebrates are those large enough to be seen without the aid of a magnifier of some kind, and these can be readily seen by divers on coral reefs. I will mention some of the most common.

Sponges

Next to colonial corals, sponges (Phylum Porifera) can be the largest invertebrates on reefs. In all, there are 5000 – 10000 species of living sponges; most are strictly marine and a great number live on reefs. Because most sponges are soft-bodied, they do not contribute to the calcareous framework of a reef, but they do contribute considerable mass. Some extinct sponges formed hard coral-like skeletons that did build reefs as old as almost 500 million years. Sponges live as filter feeders, removing tiny food particles as small as bacteria from water they pump through their bodies where they extract food particles by means of specialized cells called “collar cells” or choanocytes. Food particles can be living single-celled organisms or bits of organic detritus. By removing organic detritus, sponges act as a water recycling or sanitary system for reef waters. Many other organisms live within sponge tissues, such as arthropods and worms, and others utilize sponges as a perch or substratum, like feather stars (crinoids) or brittle stars or basketstars (ophiuroids). Many kinds of reef fish actually feed on sponges, angelfish for example.

Tunicates

Tunicates (seas squirts) are a phylum (Urochordata) resembling sponges that is very diverse and colorful on reefs. Although sponges are regarded as non-colonial animals, tunicates exist as solitary individuals or in colonies. The lump-shaped form or encrusting habit of tunicates can often lead to confusion with sponges, but tunicates have two body openings (one incurrent, the other excurrent) compared to sponges that are covered with tiny incurrent pores and a single or multiple very large excurrent openings or oscula). Tunicates also live as filter feeders.

Mollusks

Mollusks are one of the most common macroinvertebrates living on reefs. Mollusks include snails (gastropods), bivalves (clams, oysters, scallops), squid, cuttlefish and octopi (cephalopods), chitons (having 8 and sea slugs (opisthobranch gastropods or nudibranchs), as well as some free-swimming gastropods (pteropods). Many thousands of species of mollusks live on reefs, filling a wide range of ecological niches. They live as filter feeders (bivalves), predators (snails, squid, octopus), grazers (snails) vegetarians (conchs) and even as parasites. The giant clam (Tridacna) forms a large bivalved shell (> 1 m long) through the “assistance” from symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae like those in corals) embedded in the soft tissue of the mantle and exposed to light. A major extinct group of bivalves (rudistids) also constructed large, massive shells that were major reef-builders during the Cretaceous Period, probably also thanks to symbiotic algae.

Arthropods

Arthropods are very diverse and abundant on reefs, occupying many ecological niches. Arthropods (“joint-legged” include many familiar groups like crabs, lobsters, shrimp, and barnacles. Arthropods are known for their mobility, either walking or swimming. Many arthropods are omnivorous, consuming both plant and animal food, ranging in size from minute suspended items to large prey. Arthropods are also very common as commensals, symbionts, or parasites in highly modified body forms.

Worms

Worms (several phyla: annelids, sipunculids, nemerteans, nematodes) are well represented in coral reef communities. Many annelids live as filter feeders, such as colorful “Christmas tree” worms with spiral feeding tentacles, also “feather-duster” tubeworms, and spaghetti-like tentacles in others. Annelids can be free-living predators (coral-eating fireworms), sediment feeders, or commensals and parasites. Some annelids contribute to reef framework construction by building calcareous tubes, while others like sipunculids contribute to bioerosion as borers into coral skeletons.

Reef Fish

Turtles